Babies Beat ChatGPT at Physics

From Words to World models

Introduction

Christmas is the time of reflections.

Back in 2018, while taking the “Early Human Cognition” course during my MSc in Brain and Cognition, one experiment by Stahl & Feigenson (2015) really stuck with me.

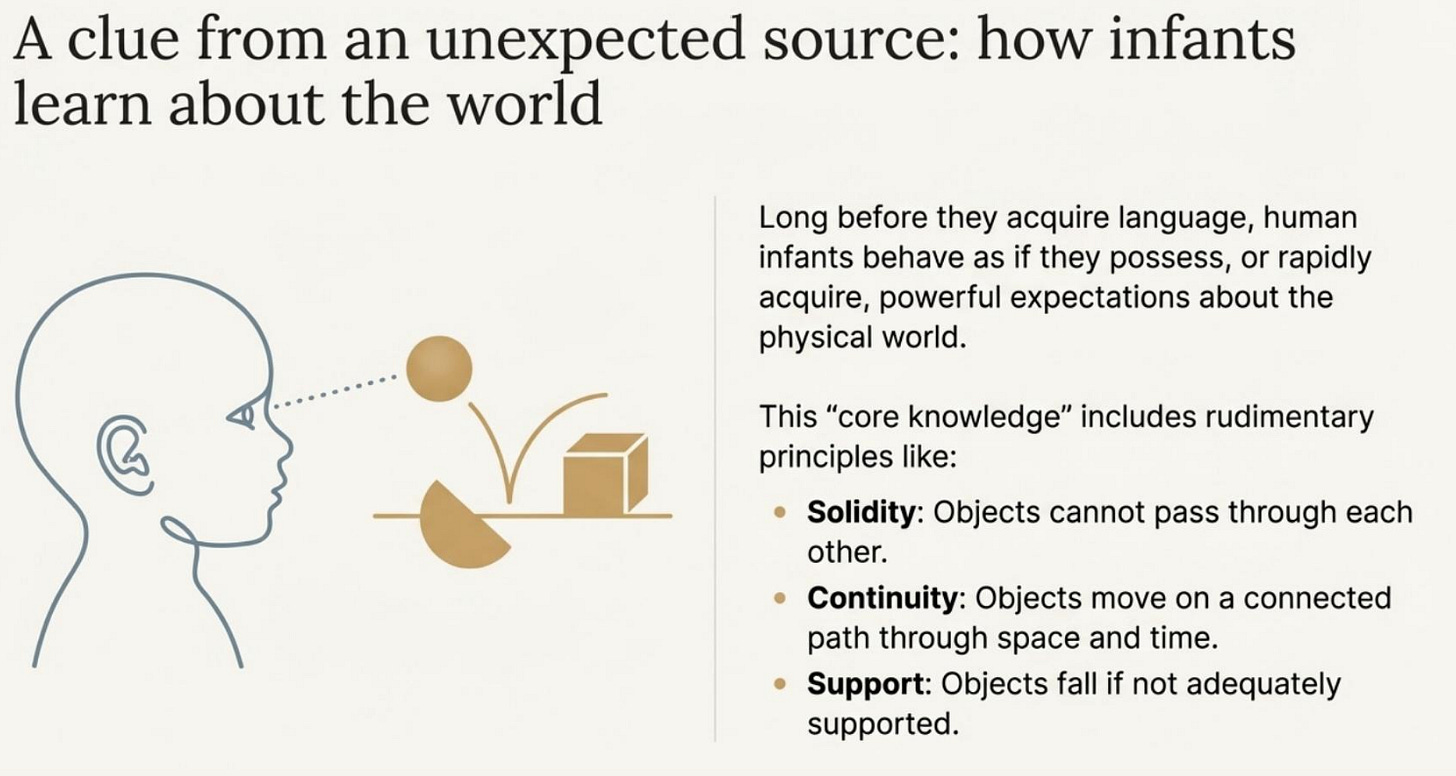

It showed something surprisingly powerful: babies do not start from scratch. They seem to come into the world with basic “physics-like” intuitions about how reality works: objects, continuity, and cause and effect.

Today, I feel like that study helped me navigate the debate between LLMs and world models. Particularly, if we want to reach AGI or truly general-purpose robotics, language alone is not enough. We need systems that build an internal model of the world, able to predict and plan. In other words: world models.

I summarized the core idea in the article below.

And on a personal note: I became a father a few months ago. Getting to observe early development up close has made this topic even more fascinating.

Video below. Link to the academic paper here. You can find the visual presentation here.

Executive Summary

This is the first research note we are publishing independently as AI Monaco. We picked a narrow but revealing question: not what modern AI can say about physics, but what it can predict about the physical world when key information is hidden, when the scene changes, or when an agent intervenes.

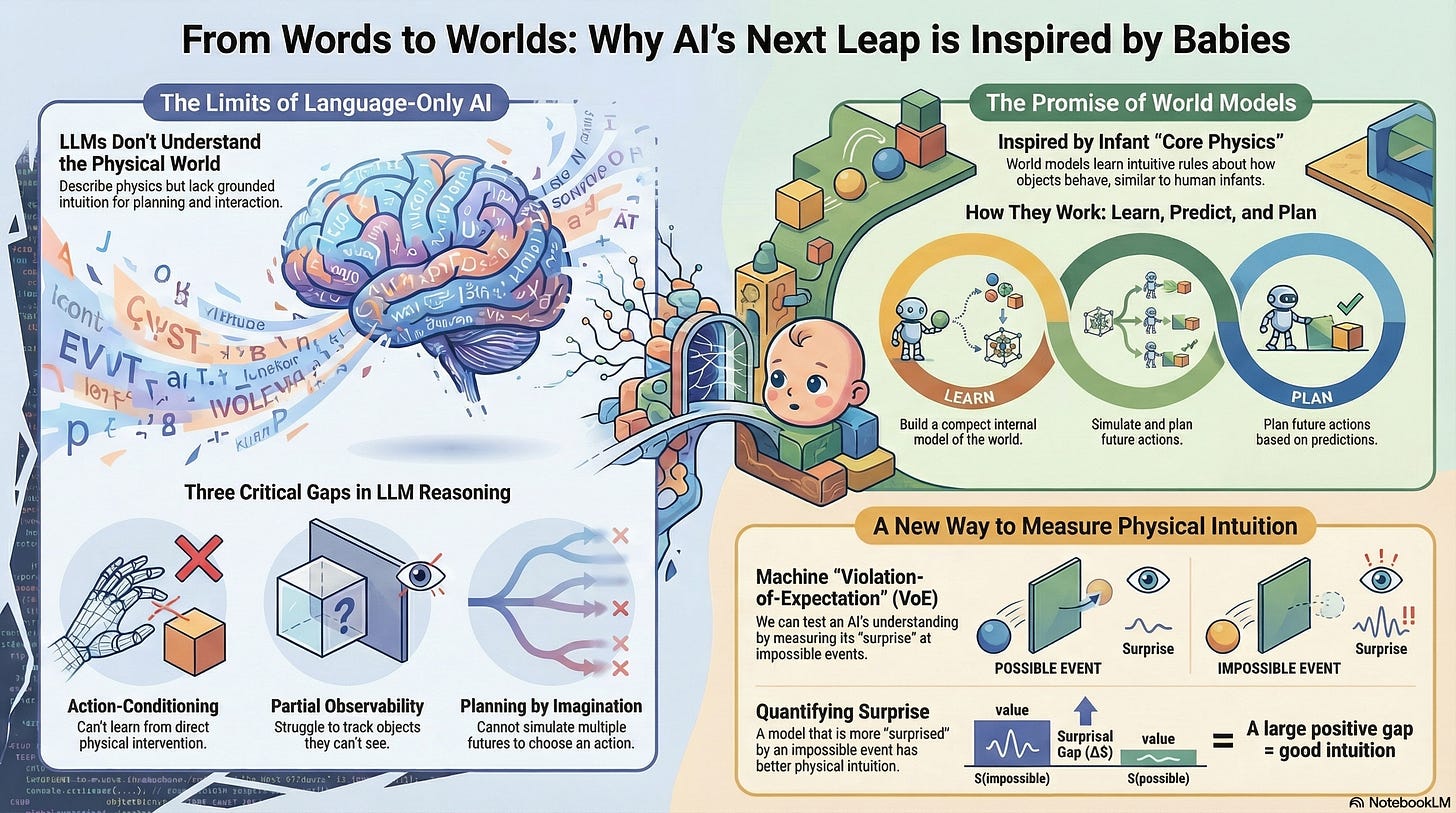

Large language models can produce elegant explanations of mechanics and common-sense dynamics, yet they often struggle when the task demands grounded prediction rather than verbal plausibility. The developmental psychology literature on infant intuitive physics gives a sharp way to see the difference. Babies, long before language, behave as if they expect solidity, continuity, support, and containment. They are not reciting facts about objects; they are behaving as if they have a lightweight internal simulator that tracks what persists even when it is unseen.

The research paper uses that observation as a mirror for AI: the core deficit in many systems is not a lack of “knowledge,” but a lack of world modeling - compact internal states and transition dynamics that can be rolled forward under uncertainty.

The central idea: “knowing” physics is not the same as predicting physics

LLMs can talk convincingly about the physical world. But physical competence is usually about what happens next under occlusion, intervention, and distribution shift. The paper argues that true generalization in embodied settings depends on predictive dynamics over compact internal states, not only next-token prediction.

What changes when we adopt that lens:

The target becomes action-conditioned prediction, not verbal explanation.

The evaluation becomes trajectory surprise, not “sounds right”.

The gap becomes measurable: do models react differently to possible vs impossible events?

Babies as a diagnostic: what VoE actually measures

Infants are not solving physics problems. They are revealing expectations. In violation-of-expectation (VoE) experiments, babies look longer when an event violates basic constraints like solidity or containment, suggesting early-developing predictive structure.

Canonical VoE patterns referenced in the paper:

Object permanence / solidity: “drawbridge” setups where a screen seems to rotate through a hidden object’s space.

Containment: events where an object appears to pass through a closed container boundary.

Why this matters for AI (and why the VoE debate is useful):

VoE is not a perfect window into concepts - looking time can reflect novelty or perceptual mismatch.

That mirrors ML benchmarking: models can “look smart” by exploiting superficial cues that do not transfer.

Why language prediction is not obviously enough

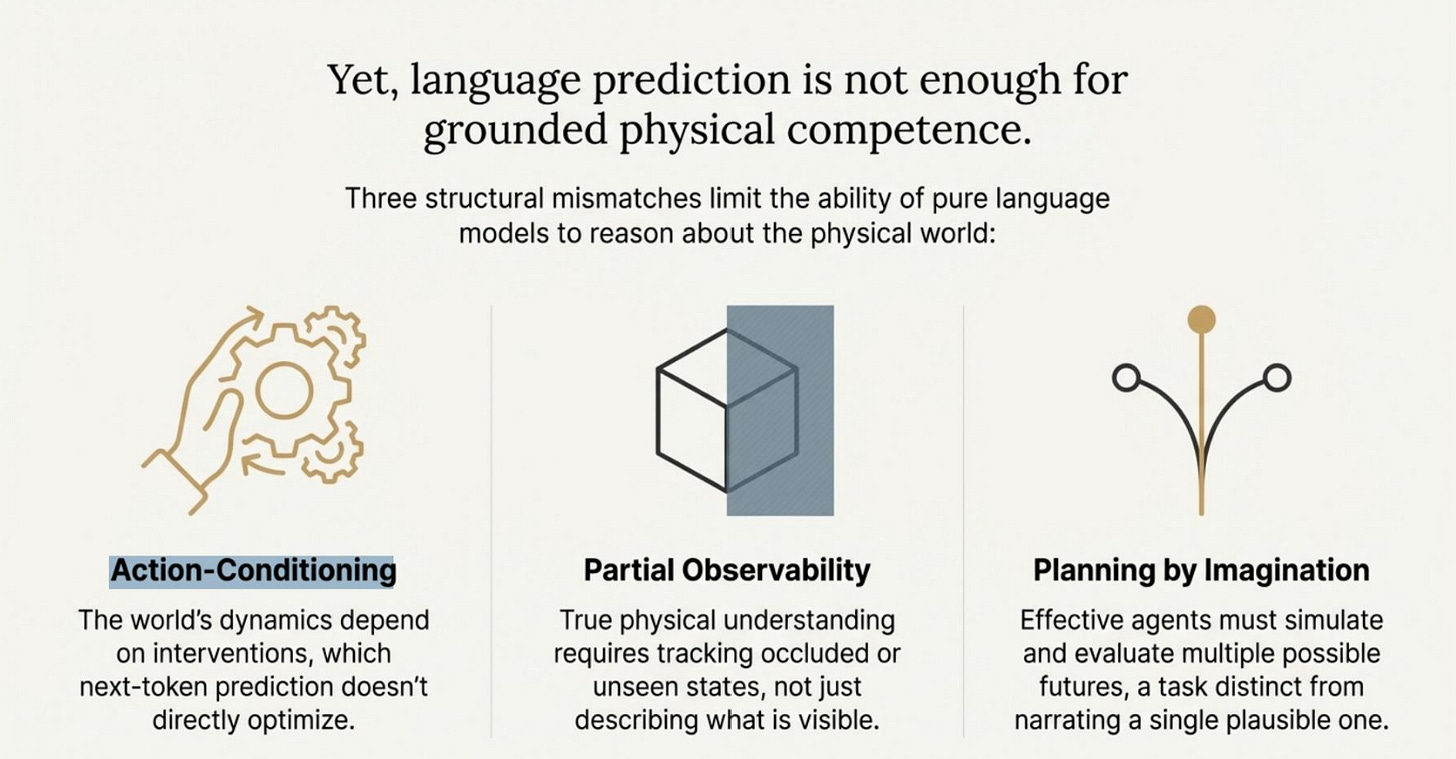

The paper highlights three structural mismatches between next-token prediction and physical competence. These are not edge cases. They are the default conditions of real environments.

The three mismatches:

Action-conditioning: dynamics depend on interventions; next-token prediction does not directly optimize transition models.

Partial observability: intuitive physics requires tracking occluded state, not just describing the visible frame.

Planning by imagination: competence requires simulating multiple futures and choosing actions, not narrating a plausible continuation.

Implication:

A model can be eloquent about physics while being unreliable at predicting outcomes when the scene is changed, hidden, or acted upon.

The alternative: world models and prediction in representation space

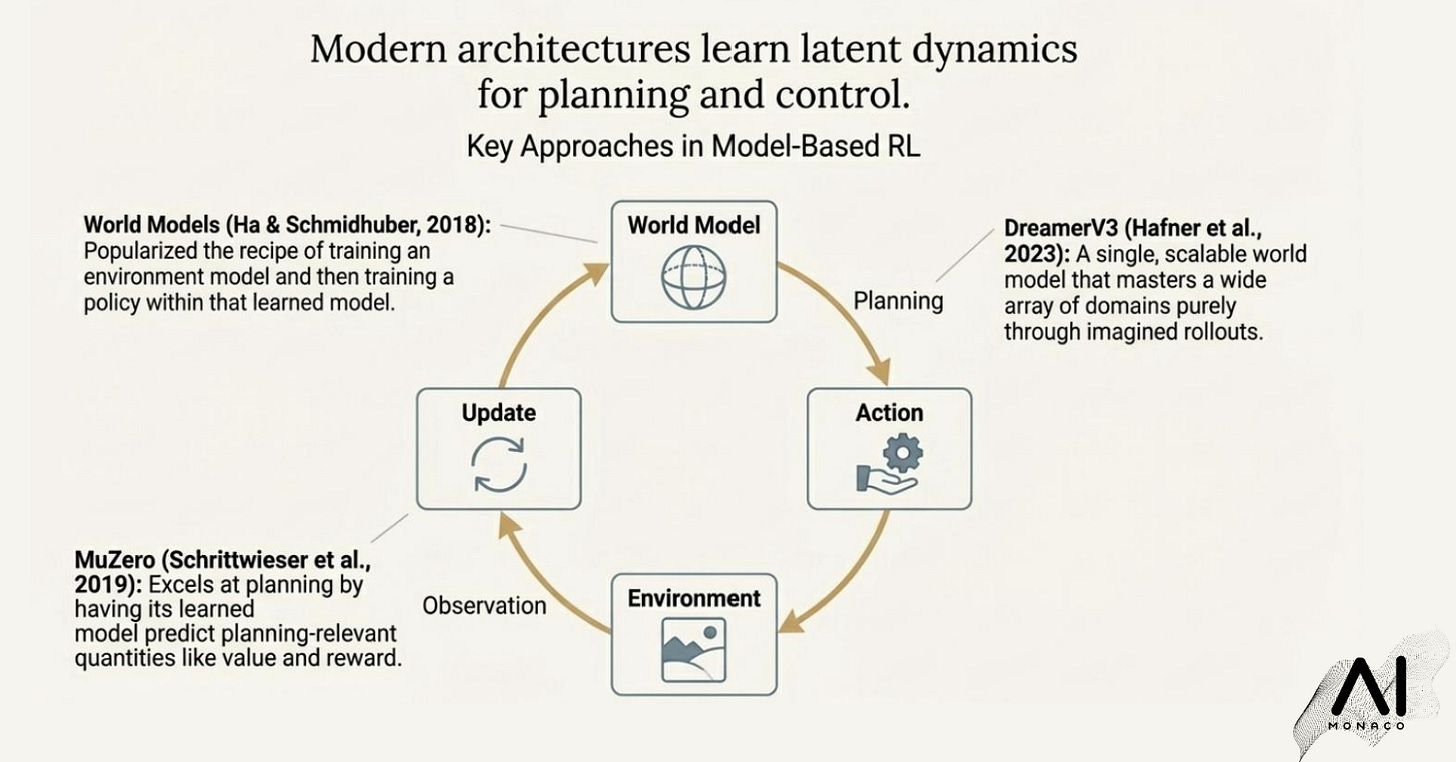

This is where world models enter as the natural complement to language. In the paper’s framing, a world model learns a compact latent state of the environment and a transition function that updates that state through time, often conditioned on actions. With that machinery, an agent can plan using imagined rollouts instead of reacting myopically. The paper points to well-known exemplars in this family, including World Models (Ha and Schmidhuber), MuZero, and more recent model-based RL systems like DreamerV3, as stepping stones toward agents that can generalize beyond surface appearance.

A key technical refinement is what to predict. Pixel prediction can be brittle and wasteful because it forces models to care about everything, including details that do not matter for control. The paper highlights Joint-Embedding Predictive Architectures (JEPAs) as a promising direction: rather than predicting pixels, these systems predict in representation space, encouraging invariances that align more closely with objects, structure, and dynamics. Work such as I-JEPA and V-JEPA is relevant here because it shifts learning toward stable abstractions over time, which is closer to what infant expectations appear to rely on.

Turning VoE into an AI test: from looking time to surprisal

The cleanest contribution of the paper is methodological: it proposes translating VoE into a machine-measurable signal. Instead of inferring surprise from looking time, we can compute surprise directly as prediction error or negative log-likelihood. The proposed metric is a surprisal gap between matched “possible” and “impossible” trajectories. If a model has internalized physical constraints, it should assign systematically higher surprisal to impossible events, and it should keep doing so when you change the texture, viewpoint, background, or object identities. Even better, the paper suggests evaluating surprisal not only over pixels but also over latent representations, which helps distinguish genuine structural learning from superficial cue matching.

This perspective also pushes toward better benchmarking discipline. The paper points to datasets and settings that can support this agenda, including VoE-style environments such as IntPhys 2, intervention-focused benchmarks like PHYRE, and language-oriented physics evaluations like NEWTON, while stressing the need for controls that reduce shortcut learning and for generalization splits that make spurious correlations expensive.

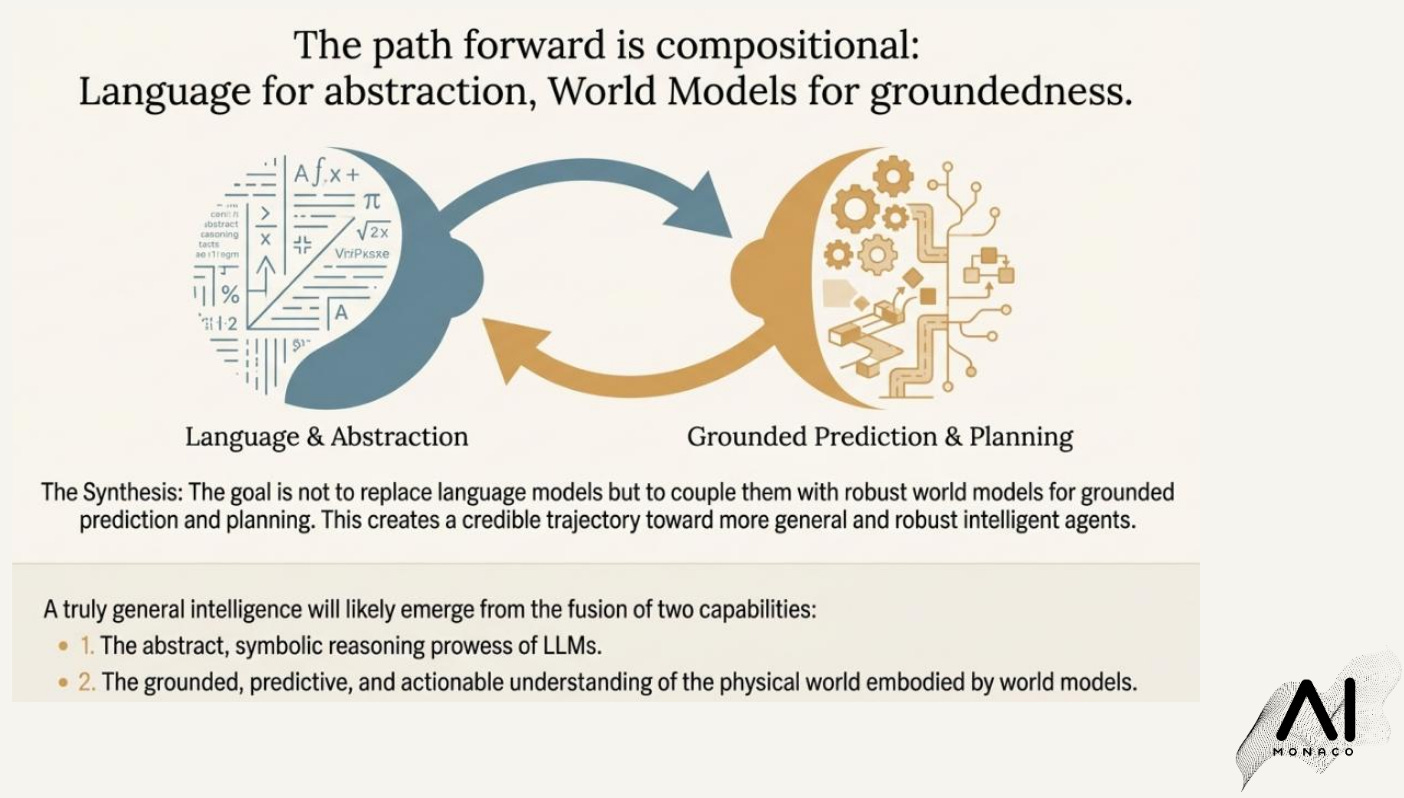

What this implies for the next generation of AI systems

If you buy the premise, the most capable systems will look less like “a bigger language model” and more like a fusion: world models for grounded prediction and planning, with language as the interface layer for abstraction, instruction-following, and explanation. The headline is not really that babies are smarter than ChatGPT. It is that intelligence which generalizes in the physical world seems to require a different internal organization than next-token prediction alone encourages. Infants are an existence proof that useful expectations about objects and dynamics can be learned early, cheaply, and robustly, and the paper’s suggestion is that AI evaluation should start rewarding that same property: stable predictive constraints under occlusion, intervention, and shift.

For the full details: Babies beat ChatGPT at Physics

Peculiar angle, great job Leonardo!